[This article was originally published in The Jamaica Sunday Observer. This online version has been slightly amended from the original article.]

Think Jamaican writers cyaan bus’? Think again! Here is a book of Caribbean stories that soars way above expectation!

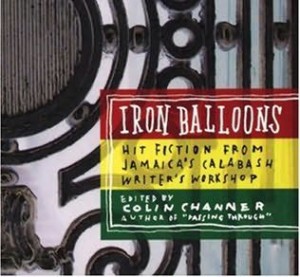

Iron Balloons is the latest publication to emerge from the Calabash Writer’s Workshops that take place in Kingston every year. The workshops are part of the initiative of the Calabash International Literary Festival Trust, a not-for-profit organisation that is working towards eradicating the perception that Jamaican writers ‘cyaan bus’’! Iron Balloons (whose title is a direct reference to this belief and is clearly ironic) is steel proof that the Jamaican literary scene is not bereft of talent, it simply lacks the opportunities.

The book begins with an animated introduction by Colin Channer (who acted as both editor and contributor to the collection) which is as long and just as engrossing as any of the eleven short stories. ‘If I wanted to be safe, dear reader, I’d begin by sharing lovely and interesting facts about the stories in this book…’ is Channer’s jubilant opening sentence. But neither the introduction nor any of the short stories that feature in Iron Balloons could be described as ‘safe’. Intriguing, absorbing, striking, contemporary: yes, but ‘safe’? Noooo Sir!

From first to last, the stories are brazenly truthful and delightfully original. The voices, styles and subjects covered are spectacularly diverse and refreshingly new. Your attention is grabbed and imagination captivated by the opening story ‘The Last Jamaican Lion’ by Marlon James. A chilling tale recounted in a direct, almost confrontational style, it tells the story of an ex prime minister who is haunted (literally!) by his past. The story is fictional but is based on Jamaica’s first Prime Minister, Alexander Bustamente, and the tale deftly describes Jamaica’s inability to realize the ideals of revolution, following the Cuban model, after obtaining independence.

A-dZiko Simba’s story, ‘Someone to tell’, is told through the eyes of a child, and is enchanting and poignant. Rudolph Wallace’s ‘Siblings’ is the only story written entirely in patois and it skilfully captures the animated rhythm of the dialect whilst exploring the realities of small-town Jamaica. Colin Channer’s account of a woman who unabashedly educates her classmates on how to beat a child, ‘the proper way’, is highly entertaining and curiously eye-opening.

The closing story, ‘Marley’s Ghost’ by Kwame Dawes, completes the enchantment. The story is set in a single room in Kingston where a heartbroken man is hiding away from the world amongst decomposing residues and is slowly but surely being possessed by his fragmented memories and life-like dreams in which he is being taken over by the spirit of Bob Marley. The writing is subtly nuanced and leaves you longing for more.

The stories in Iron Balloons encompass the entire Caribbean Diaspora and explore the pressing contemporary issues of the region. Of those that are set in Jamaica: Geoffrey Philips’ ‘I want to disturb my neighbour’ deftly portrays the angst that characterises the relationship between the prevalent religions on the island; Konrad Kirlew’s tale also uses the setting of Christianity to reveal a prevalent Jamaican situation – the vast quantity of children born out of wedlock; Sharon Leach’s ‘Sugar’ poignantly explores the pushes and pulls of poverty in an island that is constantly surrounded by the profligate wealth of foreigners.

While the realities explored are of a serious and often solemn nature, the stories themselves are recounted in a style so flamboyant, the writing infused with such rhythm, that the images leap off the page and dance freely within the reader’s imagination. In this ability to simultaneously entertain and elucidate, the stories are reminiscent of Reggae music – a music that has consistently rocked the heart of the people whilst encompassing political, spiritual and sexual subjects.

A surprising element of the book is the fact that almost half of the stories were written by tutors of the Calabash Writer’s Workshops, successful Caribbean writers such as Channer, Dawes, Nunez and Jones, not only the students of the workshops as had been my expectation. This somehow seems to go against the title of the book that suggests it is an opportunity for writers who have been unable to explode onto the literary stage, ‘iron balloons’.

Nevertheless, Iron Balloons is a collection of short stories that bursts open the usual conventions of Caribbean literature and takes it to dazzling new heights.